The Great Cellphone Saga

Somewhere in the ruins of the Urgench fortresses the cell phone dropped out of my side bag and into the hot, desert sand. It was not until we were half way back to Khiva in the car that I reached down in a panic and noticed the phone was gone. It could have fallen out anywhere! I grabbed my camera and flipped through the pictures, pausing at each picture of me wearing the side bag and then zooming in to see if the phone was still a black bulge in the side pocket. With this method, I managed to narrow down the area where the phone was probably lost to two giant fortresses and a long dirt road path leading to a lake, an area covering several miles, at the least, and several hours in the opposite direction.

I sat back in the seat as the car bounced across uneven roads toward Khiva, and after a while whispered to Mike that the phone was gone. Strangely enough, the girl next to me, Olga, was going through her bag in a rising panic and eventually announced that her mobile phone was missing! We tore through the car, reaching under the back seat (I think something is living down there!) and under the front seats, shoving empty water bottles around as we peered underneath—neither phone was located.

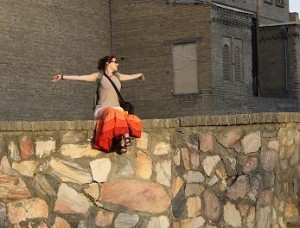

Back in Khiva, Olga and I sauntered off with our heads hung low and waved goodbye at the driver, whose puzzled look Mike tried to quell with an explanation and a good-natured shrug. While Olga later found her phone in her room, I was not so lucky. Here is what became of the phone after it was deposited unknowingly in the sand.

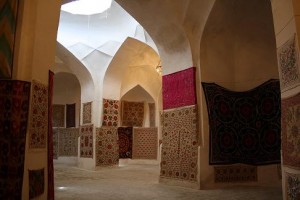

Back in Bukhara two days later I got word that someone had found the phone and pushed redial: which directed them to a friend of ours in Tashkent. I heard all this via email, where my friend eagerly explained that they were waiting in Khiva with the phone for us! Khiva is 5 hours away and we had just come from that direction, luckily the finders of the cell phone were coming to Bukhara in a few days. I tried to call the phone but the call would not go through, I tried from various phones in Bukhara and ran around the city pouring sweat until one fluent local explained that I was trying to call an in-network phone from an out-network number—“Impossible!” So, I located an in network phone (which, incidentally, is a bee-line cell phone) then called only to get the message, translated to me, “Your phone is power off. Have a nice day!”

- Chuk Chuk Tree

Before the phone mysteriously went to power off I had sent a few messages through to my friend in Tashkent about the tentative plant to exchange the phone, he had, in turn, passed parts of the message on the finders of the cell phone in Khiva. Long story short, we did not know if or when they would be in Bukhara, but Mike and I waited by Lyabi-Hauz pool from 5:30 until 9:00pm for two nights in a row wearing the clothes described to the finders, and running around to every British face asking if they had an excess of cell phones. We now have a reputation as crazies in Bukhara who wear the same clothing multiple days on end and rush around to every occupied table with wide, hopeful eyes.

It was heartbreaking to lose the phone and then the brief, glimmer of hope that had us running around in 90 degree weather and waiting anxiously by the pool for hours on end has left us even more defeated and cell phone-less.

This story, miraculously, has a happy ending. The British girl called in one final attempt as she was leaving Bukhara and left the phone at her hotel’s front desk. She even paid for that phone call since the battery on the cell phone had died. What a nice lady! And now we have the cell phone back and a great saga to tell of our first lost and found item.